How Gender Expectations Are Affecting Children's Mental Health

When five-year-old Arjun falls while playing and is immediately told to "be strong" and reminded: "Boys don't cry," a crucial lesson gets embedded in his developing brain.

Meanwhile, in rural Uttar Pradesh, six-year-old Meera is already helping her mother with household chores and caring for her younger brother while her brain is in its most critical developmental phase. When she expresses frustration about this, she's reminded that "good girls help their families".

These everyday moments, seemingly innocent, represent a larger crisis affecting millions of Indian children—one where poverty-induced childhood stress combines with rigid gender expectations to create profound mental health challenges that can last a lifetime.

How India's Poverty and Gender Expectations Are Rewiring Children's Brains

In rural areas, 48.78% of adolescent girls report symptoms of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress. But where does this prolonged mental distress come from?

Science tells us that it comes from living in extreme poverty, experiencing increased drug/alcohol use, low maternal education, and social isolation. And in India, where 84% live below $6.85 a day, most children spend their early years in conditions that give birth to prolonged/toxic stress, putting them at risk for damage to their brain architecture and lifelong problems in learning, behavior, and physical and mental health.

But here’s the thing. Every interaction during the early years is sculpting neural pathways that determine lifelong patterns of learning, behaviour, and mental health. This gives us a powerful opportunity to support our children's mental well being. But instead of providing the right support, we're unconsciously layering deeply embedded gender expectations onto already vulnerable developing minds, creating a devastating double burden.

Where do these harmful gender expectations come from? The answer lies in intergenerational transmission—parents, caregivers, and schools unknowingly passing down emotional patterns through the most ordinary moments that seem completely harmless.

Think about it: How many times have you asked your daughter to "be understanding" when her brother hits her? How often do you talk to your son when he is upset? Do you say "help mummy clean up" more often to daughters than sons? Do you say, “help dad move the big boxes” more often to your sons than to daughters?

These interactions are silently creating the neurobiological foundations for lifelong mental health patterns.

The Science Behind the Damage

When boys experiencing toxic stress are repeatedly told to suppress emotions, it leaves them with fewer neural pathways for processing emotions healthily, leading directly to the aggression, substance abuse, and suicide rates we see in later adolescence.

When girls' developing brains are constantly activated by "premature emotional labour"—managing others’ emotions, providing comfort, suppressing their own needs—, neural connections form differently, creating hypervigilance pathways that wire them for PTSD and burnout.

How We Unconsciously Perpetuate These Patterns

Mothers who grew up prioritizing others' needs above their own—often unconsciously recreate these patterns with their daughters. Northwestern University revealed that mothers who hold traditional gender role attitudes unconsciously undermine their daughters' academic confidence, asking them fewer analytical questions and providing less encouragement for problem-solving. As a result, these daughters performed significantly worse on maths tests.

Likewise, fathers who were raised with restrictive masculine norms often struggle to provide emotional support, particularly their sons. When fathers can't model healthy emotional expression, they inadvertently teach sons that emotions are dangerous whilst reinforcing to daughters that men aren't safe sources of emotional support.

Over time, boys develop brains optimized for emotional suppression and girls develop brains wired for emotional hypervigilance, both of which increase vulnerability to mental health disorders when combined with poverty-induced stress.

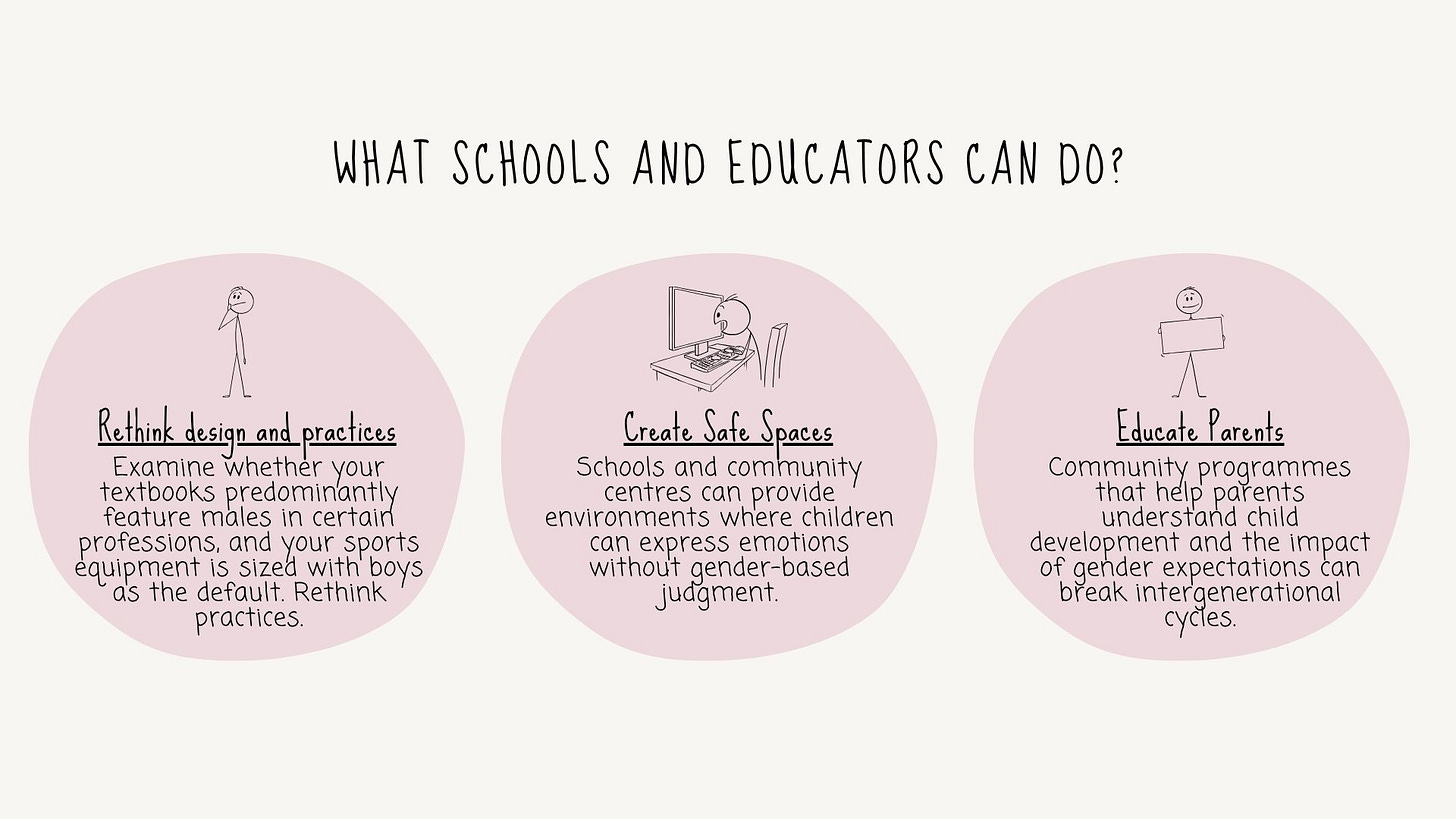

It’s not just happening in homes. Even educational institutions meant to provide equal opportunities are unknowingly reinforcing these differences through practices that seem completely normal.

Consider school uniforms. For boys, uniforms remain largely the same, comfortable trousers that allow free movement throughout their school years. For girls, increasing scrutiny over how they wear their uniform and skirt lengths fundamentally changes their physical relationship with their environment. Climbing stairs, playing sports, and even sitting comfortably becomes a source of self-consciousness and limitation.

Academic bias compounds this physical restriction. When identical tests were graded by teachers who knew students' genders versus teachers who didn't, teachers consistently gave girls lower grades and boys higher grades for the same work. This "unconscious grade inflation" teaches boys they're naturally talented whilst teaching girls they're less capable—even when girls outperform boys.

Over years, this creates permanent neural pathways of learned helplessness in girls and unrealistic expectations in boys.

Breaking the Cycle: Practical Ways Forward

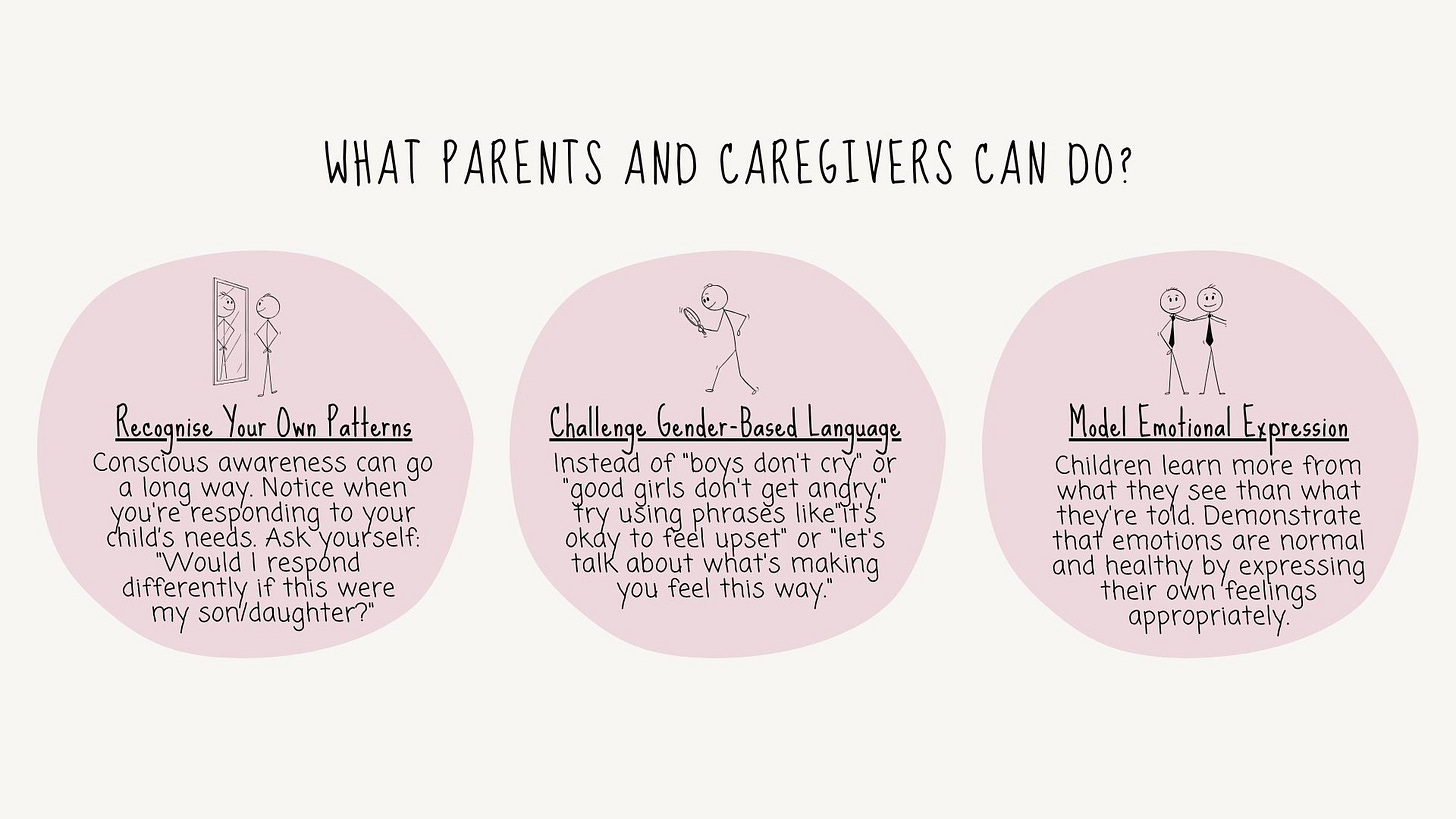

While it is true that these patterns perpetuate across generations, they can be broken. Understanding these patterns in yourself as an adult is the first step. Behaviour change campaigns that address mindsets for gender transformation at the household level (including fathers’ involvement in childcare and digital access and skilling for mothers) and equal investment in children’s future irrespective of gender can create a suitable environment for future generations.

Improving the mental wellbeing of India's children isn't just about alleviating poverty or addressing economic realities. It's about understanding the invisible intersection where economic stress meets gender expectations during the exact developmental window when these patterns become permanently embedded in brain architecture.

When we recognize and address this intersectional crisis, we can begin to create environments where all children—regardless of their gender—can develop healthy emotional regulation, resilience, and genuine hope for the future.